How Capitalism Failed Ireland

The Irish Potato Famine, the Invisible Hand of the Market, and a Million Irish Dead

To the average human, the story of the Irish Potato Famine goes something like this: Irish people ate lots of potatoes, then the potatoes got sick, then people starved, then people died. The end.

These bullet points are all inherently true, but there is much more to the story of the Famine than meets the eye. An event that is often portrayed as an act of god has much more to do with humans and markets than bacteria or science. Potatoes arrived in Europe in the late 1500s from Peru and Bolivia by way of The Spanish Conquistadors, but did not reach prominence as a crop until the 1700s.

The “Irish Famine” was very much a European famine. In fact, the destruction of potato crop was by many accounts actually worse in Belgium than in Ireland. Yet the impact in Belgium and other European nations was miniscule. So what was different about Ireland? And why did a million Irish die and as many as two million flee the country during the Famine?

To understand the Famine, you have to grasp the zeitgeist that was in the air of 1840’s and 1850’s Great Britain. This was not the Brexit Britain of today, a former world power effectively neutered by….never mind, I’ll stay on topic. Point being, 1800’s Britain was the greatest superpower on earth, and London was the finance and commerce center of the universe.

Britain had emerged victorious in The Napoleonic Wars and the new magic of the Industrial Revolution and free markets was firing on all steam engine cylinders. Free markets weren’t merely embraced, they were borderline worshipped. As historian Padraic Scanlan told me (podcast will drop next week), “Accumulation of wealth and the purchase of non discretionary goods was not just a sign of economic prosperity, it was considered virtuous.” There was a religious fervor in England around the mystical power of the market. Anything that stood in the way of the “invisible hand” was thus not only wrong from an economic perspective, it was heretical. The famine was not a marvel movie with heroes and villains, the villain was a system.

Since the 1801 “Act of Union”, Ireland had been part of the UK and did not have it’s own parliament or any legislative autonomy to speak of. Despite being technically part of the UK, Ireland was treated as more of a British colony. A primitive land with primitive people who existed to be milked for the greater prosperity of The British Empire.

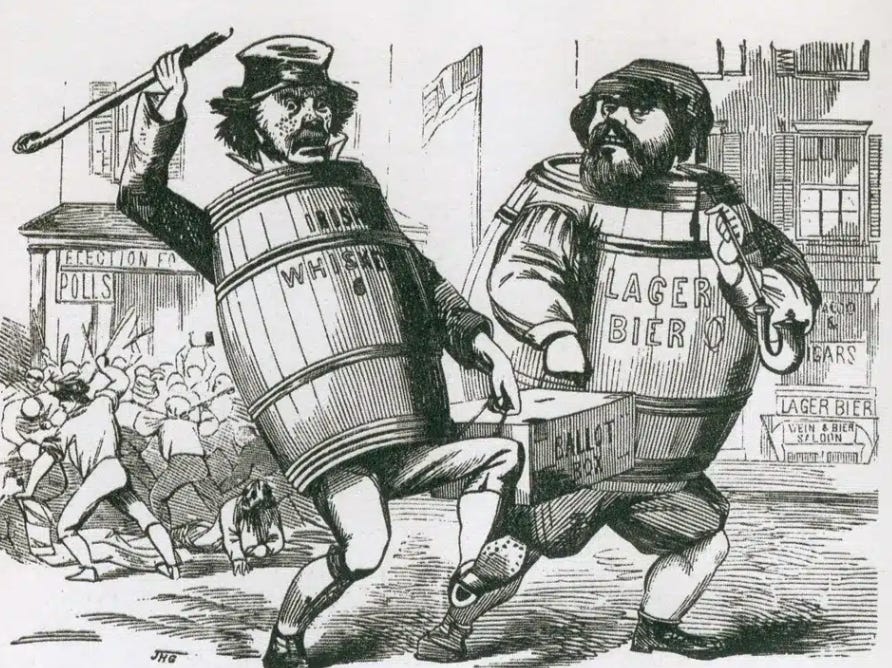

Through the eyes of the British, the lack of “production” in Ireland was equated to laziness. Ireland was not industrialized and was not producing the virtuous excess goods that the British held sacred. Therefore, they simply weren’t trying hard enough. Couple this without the outright prejudice against the Irish and you have a recipe for oversimplification of a complex problem, and disaster. Some of the Irish cartoons in the London papers from the time are disgusting, akin to some of the Jewish cartoons seen in Nazi Germany.

The Irish were in fact quite the opposite of lazy, they worked frantically to survive. And therein lies the problem….the “to survive” part. As my readers know, I am a capitalist and I am not about to go Karl Marx on you. With that said, it would be ignorant of me to try to tell the story of the famine without examining how the Irish were in many ways the victims of a capitalism British system. Let’s break it down:

HOUSING

Padraic Scanlan broke this down on my podcast as well as in his fantastic book “Rot: An Imperial History of the Irish Famine.” In England, it was quite standard for a farmer (note: “Farmer” here is more like a modern landlord than someone actually tending to crops) to purchase or rent 1,000 or more acres of farmland, rent out parcels to people who work the land, turn a profit, and either reinvest or spend/save the money. No different than a modern landlord having some cash flow left over after paying their mortgage, insurance, taxes, etc and perhaps using said profits to either improve the apartment complex or buy another complex. Capitalism 101.

In Ireland, almost all of the land was owned by absentee owners back in England who had held the land for centuries. This was often due to someones great great grandpa winning a military battle and being gifted the land as thanks. In Ireland, no Irish had the capital (more on this later) to rent 1,000 or more acres. In many cases, the top of the food chain “farmer” might rent 100 acres. The problem? The crop yield on this 100 acres was not enough to pay the rent. So parcels were subleased into smaller and smaller pieces in an effort to pay the rent. Sometimes these subleases (often referred to as “conacre” were as small as one acre.

Mix in a few middlemen getting paid between each transaction and you can see how every dime of potential profit is extracted from the system. Simply put, this is the definition of an un-virtuous cycle. The conacre system has to exist because everyone is poor, but everyone is poor because of the conacre system.

CAPITAL

In economics, nothing exists in a vacuum. Capital investment effects housing, which effects capital investment and vice versa. Simply put, there was virtually no capital investment in Ireland, only capital extraction. Given that two thirds of Irish landlords lived in Britain, there was no incentive to reinvest profits in capital improvements, roads, or the industrialization of Ireland. Ireland was seen as a place to be used for cheap labor and raw materials, not a UK territory that was worth investing in. Instead of money going into the local economy, it was virtually all extracted via rents and sent back to England to fund British lifestyles.

MORAL HAZARD

In economics, moral hazard occurs when a party has an incentive to take more risks because they don’t have to bear the full cost of those risks. In the context of the famine, the idea was that if the British gave the Irish government aide they would be incentivized to be lazy. The fear of moral hazard and the belief in the magical powers of the “invisible hand” of the free market led to the “too little, too late” response from the British government.

At the height of the famine, the British finally began importing grain (mostly from the US) to Ireland, but still insisted the the Irish people had to buy it rather than have it handed to them. If people had no money, they would be put to work in order to pay for their food. That’s right, people on the brink of starvation were doing hard labor, because…free market. In some cases, Irish would have their land seized in order to pay for their food.

An economy that is only allowed to produce the bear minimum needed to survive, a lack of capital investment, and the blind allegiance to the free market created a house of cards. Ready to be toppled by the slightest gust. In this case the gust came in the form of a bacteria from an ocean away. This wasn’t merely an economic disaster, it was a complete unravelling of the social fabric of Irish society. 25% of the Irish population was lost to either death or emigration. To this day, Irish people flee their home country in the event of an economic crisis. It happened most recently in 2008 when the standard Irish emigration numbers tripled. The scars of the famine live on.

To tell the story of the famine as an act of god and a nasty bacteria is a grave injustice. This was a human story. I’m a big believer in capitalism and the power of free markets, but there are limits. What responsibility does a nation have to it’s subjects to provide a social safety net? To see it’s people as citizens rather than a means to extract wealth? I’ll let you decide that one.

I recognize the political cartoon, made my students analyze it. The conacre system sounds a lot like sharecropping. There has to be some balance between unrestrained capitalism and government regulation.